Born and grown in The Hague, I had a younger brother Max and a large extended family with 26 cousins which we often met on holidays and birthdays. As a young woman, I got higher education in Analytical Chemistry, Agriculture, and Gardening Also, I have participated in Zionist activities such as the Gidon branch of the youth movement. Two years after the war ended, in 1948, I immigrated to Israel, and in 1951, I settled in Kibbutz Ayelet Hashahar in the Galil. The education I got before the war endorsed me to take part in building the agriculture lab at the Galil where I worked for over 20 years, providing fertilization and irrigation guidance to farmers based on soil and leaves analysis.

The war caught us in the middle of everything and unprepared for what is to come.

The year was 1942. The moment has come and we- my brother, my family, and I left the house, our house…

We close the door-we close the world to our past. We do not know when shell we will see everyone again. We went into two years of hidings at nine places. Every place, every address, and its special people… exceptional people, sure of their way, standing against the occupation and against the conceptions of the Nazis. These people with a lot of courage, the courage to help. But they did not speak about this.

During that time, I had to separate from my brother and my family;

One by one they were caught, and we lost contact.

In 1944, there was not much left of the world I knew. I was working at the printing office in The Hague, and at that time I also contacted one of the cells of the ”resistance”. Before anything happened, he has been arrested, and shortly after I was arrested too. During interrogation, it came to a point where I saw no point in keeping my fake identity. I told them who I was and that I have no family left.

I was detained in the so-called “Orange Hotel” and after the “welcome” interrogations, I was so tired I could sleep for a month. At the jail, I met Mevr Kroutsky who was the wife of the Austrian minister of treasury. She also was a lecturer in psychology. And she gave me the lectures, very good lectures, that deserve the Audience of 200 people. In return, I could teach her about Dutch history and geography as she wanted to learn more about Holland.

There were many underground inmates in the cells, which we could slowly learn as we made a small hole in the wall and had some contact with the other inmates.

I remember that there was Christmas night and the guards had a wonderful meal, the smells were all over the jail, and we were hungry, you can’t imagine such hunger. At midnight, I started hearing a holiday song from one cell, then there were more and more cells signing echoing the whole prison with the holiday songs on that cold Christmas night. What a beautiful melody. Even nowadays, when I hear Christmas songs, I remember myself in that cell hearing the melody lifting me up.

On February 45, We were transitioning to Camp Westerbork – We were put in animal trucks with some heather on the ground. War was going on with raids on roads and rails, so, the transport could move only at night, very slow perhaps 10 km/h. That trip lasted for 4 days and 4 nights. We heard the fighting outside and after two days we had a stop at Amersfoort station for the red cross gave us some food. What a sight it was, mothers were like jackals to feed their children. When arrived at Westerbork, the women's hair was cut and some felt very lost. I didn’t mind such things anymore. We were first interrogated by the Gemmeker, The Austrian camp commander. That took a few days. I was sent to the Strafbarak (punishment barrack), and my certificate was marked with S. We were dressed in Blue overall like all inmates, but we also had the letter S. At the camp, our work was to dissemble batteries and separate the paper, from the copper and the magnesium oxide. This toxic black powder went into everything, our clothes, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and inside our breathing tracks and lungs. For that, we got a glass of milk every day. But that was only in the beginning. Our handkerchiefs were all black when we blow our noses even for some time after liberation. Here we were, in the camp where the train to Auschwitz goes. We already know what that meant.

Mevr Krowsky, was acquitted with Gemmeker before the war at the Vienna Elite society, so she was classified in the “privilege” quarter of the camp, and sometimes she could bring me, in hiding, some extra food, and encouragement.

In the camp, there were row calls, morning and evenings. And sometimes at night, just to scare us. The Germans wanted the dishes to be very clean, and when a little dirt was found it was an excuse for night row-call.

I also remember Pesach evening on March 1945. We conducted a Seder, we had no matzos or food of course, but the Chazan from The Hague, Jakob Mossel was there with us. He remembered the entire Hagada by heart, and we could go over it. A small group, in hiding, sat all night telling of the exodus.

At that time, we already know that the end is close, we heard the fighting from nearby and at one point in time the transport trains stopped. One day a train came, and we were sure it was our train. But, to our surprise, the Germans went on the train- and run away.

A few hours later the Red Cross representatives entered the camp. They announced that we are liberated and free – but we are not yet to go, the roads are blocked from the heavy war going outside and there is a place to find for each one of us.

For several days we had heard the allies fighting. There were raids over and over, and we could hear and see the bombing over Groningen, a nearby city. Some people could not wait any longer and rushed out into the fighting, some were even killed.

During that time, I thought that liberation is probably not real. At night, I heard the bombing going on, and for the first time, I felt fear, I was afraid the Germans will come back.

I did not experience fear for many years now, not when I was caught and not when interrogated. You see when a man has no home, no family, nothing to lose, then there is no fear anymore, and that first night we were liberated, yet in our room in the camp, I had something to lose and I was afraid again

We were then liberated by the Canadian troops. Officially, we were allowed to go out, but the roads were blocked, and many people had no place to go to. The normal lives at the camp went under the Allies’ command. I think lives were lost at that time as people had no more patience.

The first day of liberation is unforgettable. We got white bread from Sweden, chocolate, and cigarettes too. Imagine, there are children in the camp who never know what chocolate is.

There are some people that cigarettes were so important, that they were willing to exchange the bread for the cigarettes. For me, it was unimaginable to be eating that white bread after such a long time of shortage and hunger. It was more than cakes it more than anything I have eaten in my whole life. I have been told by children that the taste of white bread from Sweden symbolized the taste of liberation for me, for us.

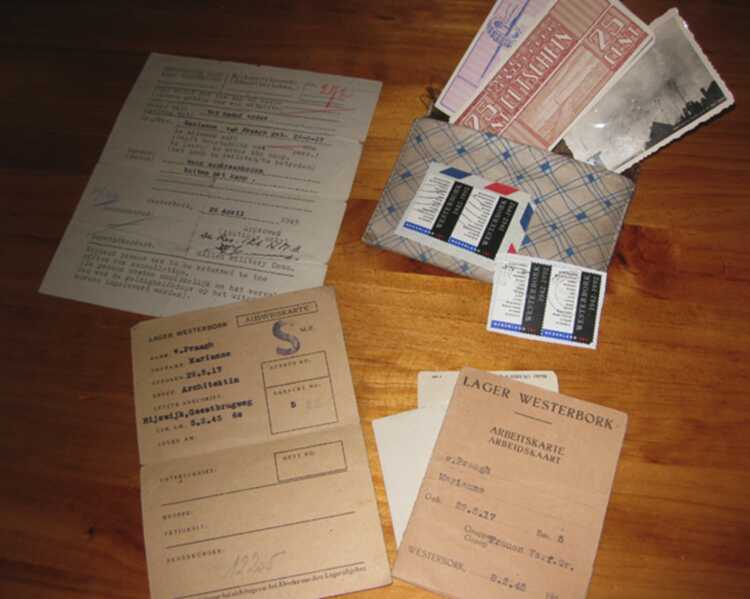

Thus, we were liberated in 1945. I kept my discharge pass along with food stamps and certificates in a small wallet. This was full of the black Manganese Oxide powder from the battery-dissembling work. I also had that picture of the parachutes and airplanes liberating that part of Holland.

There are camp newspapers, songbooks and other memorials I kept hidden all my life, I just could not open and show them to my children.

In 1945, the way back I had hopes: shall we meet again all our people? I thought I’ll go and look for them…, but there were only a few relatives who were left. Now I realize that from the moment that I closed the door of our house behind me till the moment of my return, my world had died. I returned to a world that had disappeared. And I see this world before me; this world of yesterday; the world with my mother, father, and brother, with many aunts and uncles, cousins, and their little children.

During the war I have seen expressions of in humanity that are difficult to describe and on the contrary the best sides of humanity. Very deep valleys and very high peaks.

At this moment, and not only at this moment I am very conscious of the fact that I would not stand here if these people has not been there, these men and women of the high peaks: family, friends, and sometimes strangers remarkable by their exceptional deeds.

Diklah Geva, the daughter of Miriam Bezek, had pieced together this account from things Miriam has written and told us. In February 2015 my mother passed away, almost 98 years of age. She was very much loved by her family 4 daughters and their husbands, by her 13 grandchildren, and many grand grandchildren.

Remembering Shoa and the family how lost was her command, and she left this quote for us:

“A thousand bonds tie us to the martyrs who perish in torment …

Upon us rest the responsibility to restore and make good of all that has been lost.”

Chaim Weitzman Basel 1946.